The Komechak Art Gallery

2022 African American History Month

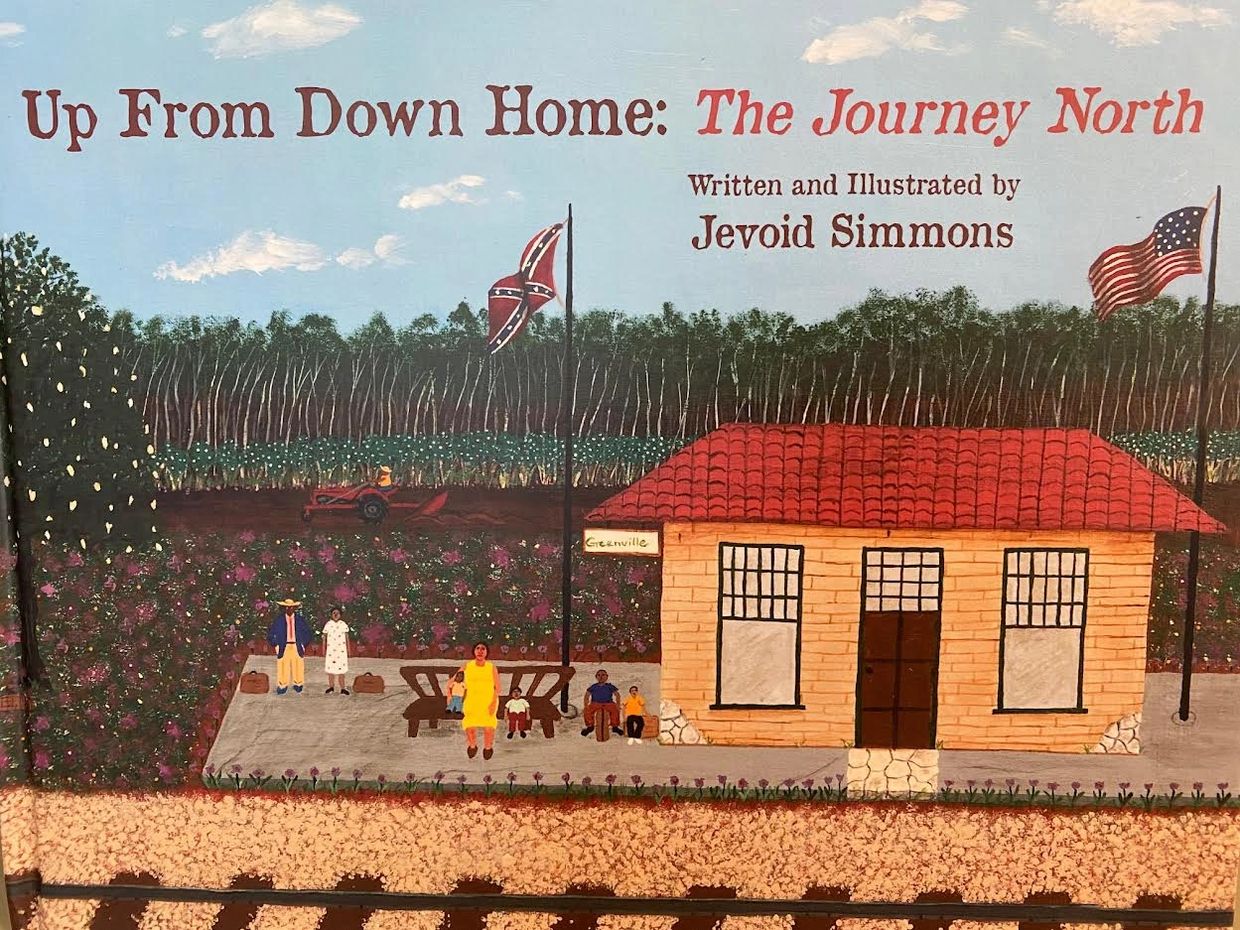

"JEVOID SIMMONS: UP FROM DOWN HOME: THE JOURNEY NORTH"

Jevoid Simmons

Jevoid Simmons considers himself to be a work in progress.

His mantra, is “I’m working to be the me I’m meant to be at this time in life” and in this segment of his life. A good deal of his time is devoted to making art which is his life-long love.

Though he has worked in a number of artistic styles, Jevoid considers his current art making to be more in line with folk and primitive traditions.

Mr. Simmons is a painter and carver, and his work has been exhibited at the Lorraine H. Morton Civic Center; Evanston’s Noyes Cultural Art Center; Evanston Art Center; Garrett Theological Seminary (Northwestern University); The Art Institute of Chicago and Creative Co-working Gallery, 1100 Florence Gallery and he has been a 40-year resident of Evanston, IL

The Exhibition and the Book

EVERYONE HAS A STORY TO TELL

Through his paintings, carvings, and now, with the release of an illustrated book, Jevoid Simmons tells the story of his of family's migration from the South to Davenport, IA and the racism that forced the journey. The artist encourages parents and family elders to share their family stories.

His collection of folk-art paintings and primitive-style carvings of friends and family members tell the story of his family's departure from Alabama, after they were threatened with violence by the Ku Klux Klan.

Simmons is one of seven brothers and nine sisters. He is the fourth boy, and last of his parents' children,

to be born in Alabama. There is a 25-year span between the first- and last-born child in his family and the older children were always told why the family had left the south, but, the younger children were never aware of the reason that the family relocated to the North.

Simmons started carving family figures, painting his memories of his time in Alabama, and writing about the family history for the younger members of his family.

In an effort to connect past, present and future generations of the family, he wanted to document the critical aspect of his family's history. His father often told his older children, "If you have no past worth mentioning, it’s possible to not have a sense of a present humanity worth defending."

Art has always been Simmons' life-long love. Currently, he is focused on police violence and the vigilantism that impacts black and brown folks.

Purchase Up from Down Home

In his newly released illustrated book, Jevoid Simmons shares his family’s migration story coming out of rural Alabama in the 1950s to escape racial violence from the Klu Klux Klan.

Seventeen paintings were completed to support the book’s written narrative.

As you view the paintings, you may see similarities to Grandma Moses’ work.

The paintings were executed over a seven-year period with the last one completed in 2015.

His hope is that the warm style will invite the viewer into the picture; while the related written narrative conveys the extraordinary hardships faced by Black folks living under Jim Crow in the South.

IT'S JUST HOW LIFE WAS

"HUMAN PROPERTY"

From the beginning, for Africans, coming to this land,

in chains, life was nearly unbearable as slaves. Property.

Most slaves coped as best they could,

creating family and a new sense of self along the way, but,

their lives were seared with acts of brutality and degradation.

Long after the end of slavery, the suffering continued,

and the wounds were seen and unseen.

For African slaves, there was a continued burning, deep within,

that was continually fueled by the desire to shout out against injustice. Yet, the over-riding individual response was a muzzled silence which was maintained, simply, for survival. Those who spoke up and sought something better, often paid a bitter price for that stand.

Hard Work: Home Training

Grandpa was a country circuit preacher and

a sometimes sharecropper.

Despite the over-riding message in the South and North

that Black folk were less than Whites, Grandpa encouraged

black people to hold their heads high. He would say;

“You are somebody; respect yourselves and your brothers and sisters”.

He called on the men to honor and protect the women,

for “No people shall ever rise above its women folk.”

A Black man speaking out in this manner threatened the social order for many Whites and scared some Blacks, as well, fearing reprisals.

I Do

Pop met Mom through Uncle Ben, one of her brothers.

He referred to Ben as his “running buddy”.

Mom had ten brothers and sisters.

Her father, Grandpa, was a farmer. Handsome and good natured,

he was liked by most folks; Black and White.

Her mother, Grandma, was a proud, unassuming woman.

They owned land and grew much of what they needed.

Pop had an eye for Mom. She was freckle-faced with a light complexion. He saw this as a good thing. Being dark-skinned,

he realized the children coming from their union would have a

lighter complexion based on her coloring. He was well aware that

the lighter our skin, the better our opportunities would be.

With little more than his good name, Pop asked for her hand in marriage. She accepted his proposal and they wed in June of 1944.

WORK CONFRONTATION: A PUBLIC REBUKE

WHAT PRECIPITATED THE JOURNEY NORTH?

It was a late evening in 1952; the end of the shift at the Chatman sawmill.

The stage was set for an event that would force the family to quit on the South

and chart a new a direction for itself, up North.

Pop, a proud young man, found himself face to face with the mill’s shop boss; a man known to be harsh with the men under his charge, and in particular his Black workers. There was a problem that arose concerning a job that they were working on that caused an argument between Pop and the boss. Some of the workers, out on the shop floor, were wondering how this disagreement would end.

My father looked the boss square in the eyes as the man lit into him in front of the men.

Pop didn’t stare blankly at the floor as might have been expected during an encounter with a White man.

This wasn’t his nature.

Pop tried to explain that he hadn't done the work, but the boss wasn’t hearing it and continued his verbal assault. Not sure if he needed to protect himself, Pop picked up a lead pipe leaning against a stack of lumber. He knew that a white boss could treat black help in any way that he would see as fit, including physical assaults with no consequences.

The boss said, "Boy, I ought to take a pipe and bust ya upside the head with it”.

Pop immediately countered with, “I already got one.”

Becoming fully aware of his situation, the boss high-tailed it out of the shop with Pop in close pursuit.

TROUBLE HEADING HOME

"CONFRONTATION ON THE ROAD"

Heading home after his encounter with the shop boss, the road was dark and deserted. Pop was troubled; he knew what he’d done wouldn’t be forgiven or forgotten.

The backlash started immediately. Blocking the road ahead was a truck with its bright lights on. He couldn’t pass on either side without going into a ditch; it had rained that evening.

Given what happened earlier, he knew this was the start of trouble.

He checked the pistol he carried in his lunch pail for protection.

He got out of his truck, with the pail tucked under his arm, and faced them waiting for their move. One called out, “What you think you doing chasin at a White man like that boy”, referring to the shop boss. Another shouted, “What you got in that lunch bucket?"

"If I have to go in it, I aim to use what’s in it”, Pop replied.

They backed away. “This ain’t the end of it boy,

we’ll be seeing you again”.

My father, also, knew it wasn’t finished.

The men got back in their truck, as did Pop.

Each party gave ground on the road allowing the other

to move on into the night.

"TROUBLE COMING"

Despite the racially charged climate of the South in the early 1950’s, there were strong bonds among some folks that even

crossed the color line. One such relationship would prove

to be crucial to the family’s survival.

An older White man who’d known the family for many years may have been a guardian angel. Being neighborly, Pop and two of Mom’s brothers had dug a well for him at an earlier time.

Several days after the confrontation at the mill, the old man

came to the house with a warning.

“There’s been talk roun town bout ya”.

He said, “Jimmy you gotta get out, the night riders gonna

come for ya and they aim to do ya in”.

The old man took a serious risk simply doing right by his neighbors. With this act of humanness, our family survived.

"SHE'S FOR SALE'

Most important was getting everyone out of harm’s way

before it was too late. This meant we had to get out of the family home as quickly as possible.

Finances were tight, so options were limited.

On the positive side Pop could be fairly resourceful and

had the ability to approach problems in a pragmatic fashion.

He needed money and had to come up with it quickly.

Only a few weeks earlier a man had inquired about buying a cow

he’d seen grazing on our property. The next morning Pop looked

the man up to see if he was still interested. Luckily, he was.

They haggled back and forth and, eventually,

came to terms on a sale price.

It was enough to get out of Alabama.

Pop had kept an important detail from the cow’s new owner.

It wasn’t ours to sell.

THEY CAME FOR MY POP

"GRANDMA'S PLACE"

Mom and Pop gathered the essentials for our stay with her mother. We knew her as Grandma Ollie.

Grandpa Pearlie had died two years earlier.

Everythingwe needed was packed because it would be too dangerous to return to the house. With us in tow, it was off to Grandma’s house.

As would be customary for Pop, we were admonished to

behave and be useful while we were in her home.

He assured Mom that everything would be alright

and that he’d send for us as soon as he could.

"REFLECTIONS"

Satisfied the family was out of danger,

Pop returned to the old place to prepare for his journey.

There alone, with us secure at Grandma's house,

he had a little breathing room and a chance for reflection.

I imagine that there in the quiet,

he would’ve have been flooded with memories.

The family we were to become started in this little house

with two individuals who couldn’t have been more unlike

in disposition and background.

"STEAL AWAY"

Money in hand, Pop left for the train station.

It was the start of a journey filled with the promise of

new opportunity away from the trouble being faced.

Waiting for the train to depart, he kept to himself

to avoid drawing any unnecessary attention.

The train left out that evening.

He arrived in Rock Island, Illinois the following day

and was taken in by Aunt Mary and Uncle Wilbert.

"NIGHT RIDERS"

After Pop caught the train, just as the old man warned,

the Night riders paid a visit to the family home.

Finding no one there, they ransacked the house.

Later, we learned of the visit through friendly channels

and never returned to the house again.

What would’ve been our fate had we been there when they arrived?

Knowing Pop, he would’ve fought to his death defending the family.

Our lives, like so many others, would’ve been altered, forever.

We would have been filled with pain and thoughts

of what might’ve been.

NIGHT RUNNERS

THE EXODUS OF BLACKS FROM THE SOUTH

Between 1915 and 1970, approximately, 6 million Black Americans got up, packed the little they possessed and said goodbye to the South.

The exodus happened in waves.

The first, often referred to as the Great Migration, began at the outset of World War I and continued through the decade that followed the War’s end. The destination was the urban centers to the North. Approximately, 1.5 million departed during this period.

The second wave began at the start of World War II and continued up until 1970.

The destination continued to be urban cities to the North, and increasingly,

major western cities. It’s estimated that 4.5 million Black Americans left the South

during this time.

There was no grand plan that guided the migration; rather, it was individuals and families making decisions on how to secure a better future. This meant putting distance between themselves and a Southern system that was overtly hostile to them.

It was an act of survival.

Some had time to plan their departure.

Others left just ahead of a rope thrown over a tree limb.

THE JOURNEY ENDS IN IOWA

"CHICKEN DELIGHT"

When he arrived up North, Pop got his bearings and secured work.

He hired on as a cook and general helper at the

Chicken Delight restaurant in Davenport, Iowa.

Despite having come to a place far better than where he’d been,

he quickly learned that “Jim Crow” thinking was alive and well

among some white folk living in the North.

He was able to work at the restaurant, but not allowed to enter through the front door like the white workers and patrons.

Black folks, who came to get a meal, also had to enter through

the back door and eat in the back area of the restaurant.

It was insulting, but, he endured it for the family.

"REUNITING FAMILY"

In Alabama, other parts of our extended family were heading north to find work. Uncle Daniel, one of Mom’s brothers, had taken his family to Albion, Michigan a year earlier. Their departure was particularly difficult for Johnnie and Clarence, my oldest brothers.

When they left, there was a great sense of loss.

They lost the community and family they had grown up with.

It was almost a year before we were together living under one roof. Pop sent money back home to help support us. He did this while scraping together money to bring us North and

contributing to Aunt Mary and Uncle Wilbert’s household.

When word came that it was time for us to head north, there were mixed feelings. As much as Mom wanted the family together,

she was taking her children to live in a place far from her people.

"SISTER'S LETTER"

My earliest recollection of life in the North was of our first apartment.

Making it livable had to have been a challenge for Mom. It was in an unfinished basement of an old house that had a dirt floor.

To make it more comfortable, Mom bought an old rug to throw over the floor. It wasn’t the best, but it was home, and we were together.

A few years after our arrival in Iowa, Pop secured employment

with the Rock Island Arsenal as an electroplater.

This position created enough security for the family

to put a down payment on a house in 1955.

Excited about our new home, Mom wrote her sister back home saying, ‘My dear sister, we’ve found the house where we will raise the family.

Twelve more children would be added to the family in Iowa.

DAVENPORT, IOWA

THE HOUSE AT 1404 CHRISTIE STREET

The house was in a good neighborhood filled with children carrying the names:

Dixon, Scott, Camp, Green, McNeal and Jenkins.

The house has an interesting history.

It sits a half mile from the Mississippi River.

It was rumored to have been a stopping place for slaves who escaped the South

and continued their northward trek to Canada. Reaching Canada, they could avoid being returned to bondage under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The kitchen had a trapdoor to a dry well that was said to have been connected to a corresponding exit point in the back yard. Shoes and clothing from a long-gone period were found in the well and dugout area under the house that served as a root cellar.

The house has remained in the family almost 70 years.

Willis Nathanial (Bill) and his wife Renee are its current owners/caretakers.

At 1404 Christie Street there was joy, laughter and at times stinging tears.

But most important, there was love in the home.

And the story continues …

"FAMILY REUNION"

With Pop and Mom having passed on in 1973 and 1976 respectively,

all of the brothers and sisters came together for a family reunion.

This was the last time that all of the brothers and sisters would come together on this side of life.

NEW WORKS

“Rest In Peace Rodney King”

This painting is an interpretation of the brutal police beating of Rodney King on March 3, 1991.

The officers involved were acquitted.

Why were they not held accountable for this violent act?

Is there something embedded with our systems that requires this extreme action?

What would’ve been the outcome if King had been a young white man?

Thirty years later, this kind of extreme violence is carried out on black and brown folks by police and vigilantism.

Know their names:

Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland,

Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor and a whole host of others.

King’s treatment, and the that of others, is a manifestation of deep-seated racism whether conscious or unconscious.

The impact is the same; catastrophic devastation and suffering in families and communities.

Dimensions: 24" x 36" x .5” acrylic on canvas

Completed March 2021.

"THE BURIAL"

Racism in this country fueled economic development with unpaid labor of enslaved black people and land stolen from indigenous people.

This is an ugly truth many people would rather sweep under the rug.

The thought is “let’s just move on”.

Moving forward without addressing this issue is like ignoring a malignant tumor in the body.

There is no healing without dealing with this truth.

RACISM IS STILL ALIVE AND WELL IN AMERICA!

It’s entrenched in our institutions and is embedded within all of us.

I don’t believe it can be eradicated without people, who are white, acknowledging this truth.

Then, with this understanding, take on the heroic task of confronting racism, privilege and supremacy.

The Burial is a symbolic representation of this needed action.

The painting is not a condemnation, rather it is a loving call for this essential work.

THE TIME IS NOW!

THE CARVER

THE FAMILY

There's a 25-year span between the first- and last-born child in our family.

"The older kids, me included, were told why our family left the south.

But the others weren't aware of it.

So I started carving family figures and writing about the family history for my younger siblings

and then started writing narratives and documenting the critical aspects of our family history.

It was an effort to connect past, present and future generations of the family.

Pop often told his older boys:

"If you have no past worth mentioning,

it’s possible to not have a sense of a present humanity worth defending."

Watch A Video

Artist and Storyteller

Jevoid Simmons Shares His Family's Legacy in "Up From Down Home."

About the Video

EPAC members, Fleetwood-Jourdain Theatre and The Musical Offering, are collaborating with Evanston artist/storyteller extraordinaire Jevoid Simmons and Theatre Zarko's master puppeteer Michael Montenegro. Collectively, they are bringing to life the true story of Jevoid’s family’s audacious journey from the Jim Crow South to the urban North in the 1950s.

In this heartfelt storytelling, animated puppetry presentation, Jevoid uses his melodic voice and subtle inflections to beautifully share a portion of his newly released book

"Up From Down Home: A Family's Journey North."

Montenegro’s imaginative animated puppetry supports the folk story with stunning visual creativity. Harmoniously floating underneath are the original musical compositions by The Musical Offering’s artistic director Rick Ferguson.

Directed by Fleetwood-Jourdain Theatre's artistic director Tim Rhoze, this exquisite EPAC Performing Arts Installation is just one more way Evanston performing arts organizations and artists are giving back to the community.

Click on this link to view this amazing video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ickDJ3-Vi74&t=80s

Note: You will be directed away from this website

Contact Jevoid Simmons

Copyright © 2022 The Komechak Virtual Exhibitions & Programs - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder